Portraits you know, photographs you don’t, sights you’ve seen but can’t recall, half-remembered lyrics, bygone eras, and recognising the sound of a gramophone without knowing what one looks like.

‘The Unknown’ of 2014’s Over the Garden Wall is less than it at first glance claims to be. An autumnal landscape which, like any fairy tale, is navigated by two children lost in the wood; Wirt and Greg. Stumbling upon a hell hound in a grist mill, a manor house with a dispossessed man, and frog lullabies upon a ferry, all in their long walk home. Through this world, creator Pat McHale establishes a ‘geographic storytelling’, wondering the blurry lines of the show’s central question: where do unknowns end, and knowns begin? Our hero Wirt navigating these nuances like trees in a wood, on a pilgrimage to nostalgia.

Motifs of nostalgia, memory, and false-memory are ingrained within each of the show’s ten chapters, conveyed across a variety of forms. You may have heard the show’s title already from the late twentieth-century rope-skipping rhyme:

‘Over the garden wall

I let the baby fall.

My mother came out

And gave me a clout

Over the garden wall.’

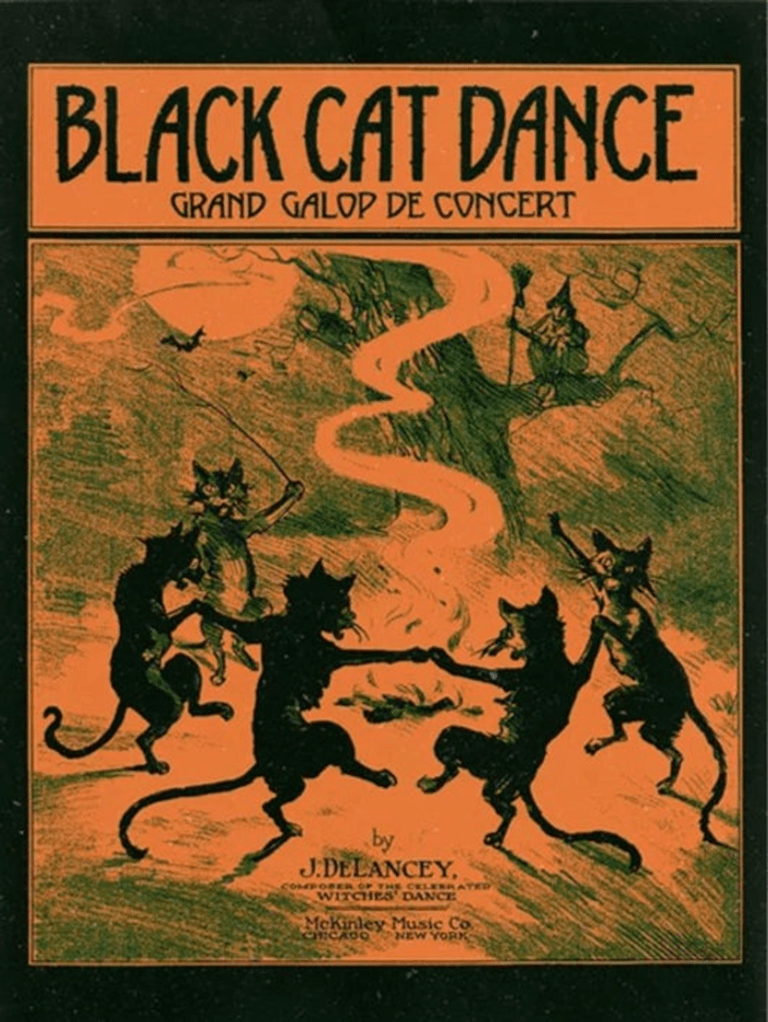

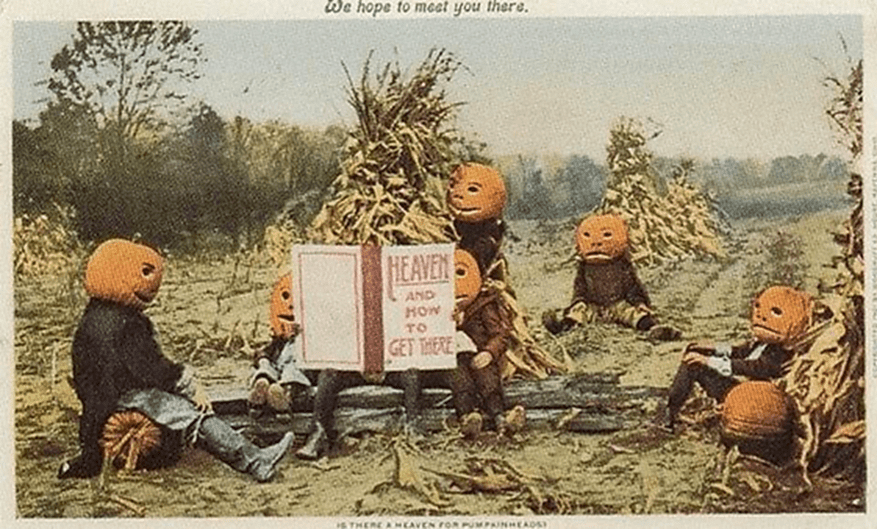

Anyone familiar with Beatrix Potter may see the resemblance between her illustrations and the animals of Chapter 3’s School Town Follies. Lullaby in Frogland, too, pays homage to the game art of the McLaughlin Brothers’ Frog Pond. Betty Boop and the Tavern Keeper, Oz and Cloud City, the Black Cat Dance music cover and the Pottsville skeletons…the list goes on.

A key musical cue, Come Wayward Souls, and its subsequent Potatus et Molassus lead the march in a symphony of reiteration in their similarities with Christian hymn O’Holy Night. The show’s Old Black Train becomes Woody Guthrie’s The Little Black Train, The Fight is Over becomes T.Rex’s Ballrooms of Mars, and The Highwayman becomes the Disney animated St. James Infirmary Blues. Every frame and track eerily familiar to things seen and heard before. Lyrical adjacencies ticking away in the subconscious: rhymes. And through this use of memory ad recognition, McHale has audience and characters alike travel through time as well as space, with references shifting from the 1600s, through the centuries, to the 1900s. The show even superseeding its true ’80s setting in its final shot; pulling out on the city landscape of Cartoon Network’s (as of then) unreleased contemporary show Clarence.

Though The Unknown is commonly speculated to be limbo, it is perhaps a more metaphorical abyss. A space, instead, between the familiar and the unfamiliar; known and unknown. A collage of Americana artwork, and a composition of Americana concerto. Even the brothers’ fall into the riverbank – transporting them from their ’80s-set home to this purgatorial timeless landscape – references a more literal interpretation of an ‘uncanny valley’. And their destination, that of a wood, is itself a cacophony of the same sights and sounds across a vast vista – the visual similarity of trees evoking disorientation in any fairy tale. Lost forgotten stories, brought together in their structural and moral similarities; their rhymes.

The infantility of these half-recollections speaks to the motifs of children’s literature – but it also warns against the snare that is nostalgia. To fall into a place somewhere between reality and memory, and become lost. Unable to leave until one faces reality, surpasses the fables, and accepts the world for what it is, as Wirt – ‘The Pilgrim’ – does.

That ’80s setting is not for nothing, considered by many as the most revered and longed-for bygone era. A cultural yearning to return to the past is highly precedented, however for a memory to persevere through generations, is less so. With Generation Z of Western demographics, never having lived the ’80s, longing for it. Memories of memories. Copies of copies. And with reiteration comes degradation. Lines unblurring from facts and dates to reveries and vibes. This, laid bare, is the machine of nostalgia. Driving the Woodman to madness – lost in his own way – and Wirt to confusion and depression. This is the land that The Beast – the devil of McHale’s purgatory – inhabits. One in which children are grinded into fuel, to sustain the soul of something long-dead and grotesque. This is the cry of Pat McHale, and the cautionary fairy tale of a new generation of storyteller: ‘Beware the unknown‘.

The slights between memory and folk-memory can be navigated only by you. Memories, like stories, are no one thing, and form no holistic miscellany; they are varying and mercurial, kaleidoscopic and untameable. No bigger a wood could one imagine, and with each map esoteric, how could anyone be but lost. However, it is not the extinguishing of The Beast’s soul-sustained dark lantern that resolves Wirt’s dilemma, but the repurposing of it to what it was intended as in the first place: illumination. Guidance from the dark of the unknown, to the light of the known. Indeed, as McHale himself observed, ‘Maybe all our memories are lies. Maybe everything we perceive is a lie. But we have to put our belief somewhere. Right?‘ Or something like that. This is what a gramophone looks like, by the way.

The Unknown is not where our horrors live, for nothing knowable may reside there. The uncanny is little more than resemblance, and autumn is but the ghost of winter. Instead, it is The Known we must face. And put nostalgia to bed. As the show opens with, ‘Somewhere, lost in the clouded annals of history, lies a place that few have seen – a mysterious place, called the Unknown – where long forgotten stories are revealed to those who travel through the wood…‘

Harrison Whittle.

Leave a comment